Written with Dr. Andrew M. Durso, author of

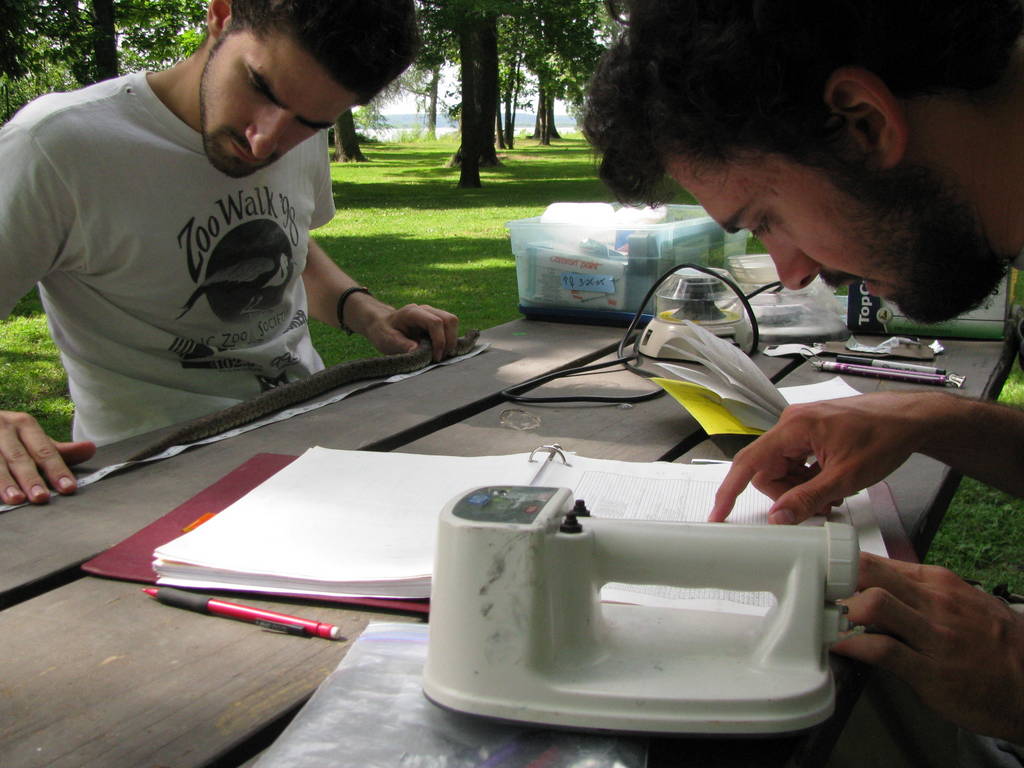

Life is Short, but Snakes are LongQuestions about the natural world continually arise during fieldwork or laboratory observations, as well as from existing publications and discussions with the public or other scientists. When these questions appear to warrant further investigation, biologists follow specific steps to seek answers.

The first step, once a question has been identified, is to form suppositions as to the likely answer (hypotheses). Scientists then envision what tests might be performed to disprove these suppositions. If completed tests fail to disprove a hypothesis, the results are considered supporting evidence, but scientists are careful not to refer to hypotheses as “proven” because future experiments might find another way to disprove their suppositions. They perform these tests and, depending on the results, adapt their approach to delve further with additional testing. Once they have results, they draw conclusions, identify further needed research, and share their findings with their peers. Other scientists then review the methods used and conclusions drawn, and their research is (hopefully) published in a journal. This process is how we develop trustworthy information about the world around us.

Research often begins by examining what others have done to gain more understanding and to verify that someone else has not already found the answer. What data already exist? What methods were used to gather this information? What tests were performed and what results were produced? This information typically comes from previous publications and discussions with other scientists. If questions remain, the next best step is usually to collect a small amount of data or perform an initial trial (known as a pilot study) to determine better whether investing resources into additional research is warranted and feasible. This may be done in conjunction with experiments already underway, through computer models, through further analysis of existing data, or other methods. This pilot study then becomes the basis for a grant proposal to conduct a full study.

The next step—securing the funding for more thorough experimentation—can be tricky. Science generally doesn’t pay for itself; grants normally come from governments, universities, or private foundations. Scientific grants vary in size from a few hundred dollars to more than a million dollars. They are always awarded for specific projects, and the money goes to an institution (such as a university) rather than to an individual. These funds are necessary for items such as paying students and technicians to carry out the work, buying equipment and supplies, and paying for travel, food, and lodging while conducting fieldwork. Finding funding often requires several attempts over months or years, and most grant proposals are rejected. Once funding is approved, the next challenge is getting permits to perform your field or lab work from any applicable governing entities.

The actual research and experimentation may take months, years, or decades. Longer projects may need several rounds of funding. During this time, the grant proposal is the roadmap and should be adhered to unless new data indicate that changes are warranted. Research often takes longer than anticipated, either because it is difficult to predict what one might find, or simply because life happens: harsh weather, political changes, personal difficulties, etc.

Once collected, data are formatted, organized, summarized, graphed, and analyzed to make them easily accessible. Do the data rule out or support the original hypothesis? What conclusions do any unexpected results lead to? What uncertainties remain? Scientists often repeat and expand their research once the data are analyzed. These steps must all be performed before submitting the research for review (which we will discuss in the next post).